Introduction: Is Holistic Nutrition Legit?

Introducing a special new series - The China Study Controversy

When I was in college studying to become a Certified Health Coach (or, as my official title goes, Healthy Lifestyle Counselor / Natural Nutritionist), the centrepiece of the second semester was a course called The Natural Doctrine of Nutrition from a Holistic Perspective.

I figured the course would discuss the energies of various foods and their combinations (and hopefully finally explain what on earth “energy” means), the dietary wisdom of indigenous cultures, and the deep connections between food, mind, spirit, and life itself.

When the course arrived, however, I was surprised – and a bit disappointed – to find that, like the Introduction to Nutrition course in the previous semester, this course too was mostly based on science, with only a bit of holism and traditions sprinkled around, almost as an afterthought.

After introducing the evolutionary theory of dietary habits, we dove straight into the nutritional profiles of every grain, fruit, and vegetable. There was some mention of the cultural origins of various foods and unconventional diets (such as raw food), but we mostly memorized tables of fiber contents and glycemic loads. Even the semester’s most holistic slide presentation, the yin-and-yang-based Macrobiotic Diet, needed to be dressed up with that sciency-sounding name.

If holistic nutrition too is learned in scientific jargon, I began to wonder, how is it different than conventional nutrition?

But as the semester went along, I noticed that the “holistic science” was cut from a different cloth than the macro- and micronutrients we had learned about in the previous semester.

Whereas the first presenter, a university-trained dietician, stuck to established science, always careful to keep the data in its original context, the second seemed far less rigorous. All sorts of research was tossed around about the virtues of this vegetable and the dangers of that industrial additive, but when I looked up some of them online, they often came up as low-quality studies or only clinically relevant after making some unproven assumptions.

Is holistic nutrition merely the discarded leftovers of real science? Isn’t that the definition of pseudoscience – a claim made out to be scientific which really isn’t?

My mind went back to the program’s opening lecture about the historical roots of natural healing, all the way back to the four elements of ancient Greece. However, the college administrator concluded, we’ll be learning in the language of modern science. Already then I had felt uneasy. Language is an important thing: how can we study a discipline that predates modern science in the terms of biochemistry?

The China Study

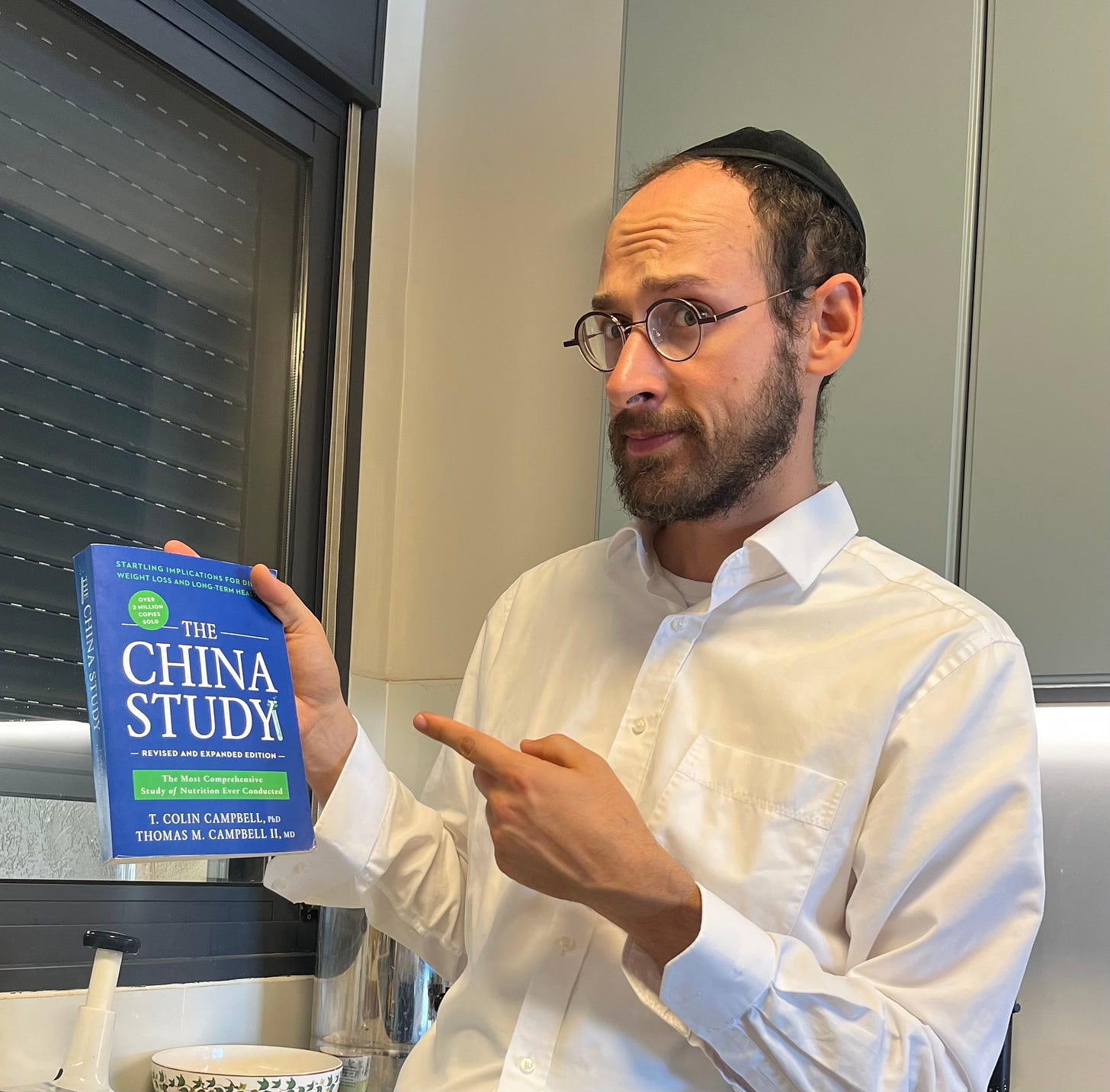

One of the primary sources for the holistic nutrition course was the China Study, a huge 1980’s observational study in rural China directed by Dr. T Colin Campbell, which purportedly showed the dangers of eating all animal products and the benefits of eating whole, unprocessed foods. The study remains one of the most popular scientific sources for the popular Whole Food Plant Based (WFPB) diet. Its namesake book, The China Study, republished in 2016, has sold millions of copies.

Moreover, it seemed that The China Study, and its sequel-of-sorts, Whole, delved deeply into the larger questions I was interested in.

What exactly is nutritional science – is it only the molecules I eat, or how and when I eat them?

Does it teach about lifestyle habits related to metabolism, such as exercise, perhaps suggesting whether to work out before or after a meal?

Where does empirically proven science end and the more intuitive holism of healthy choices begin?

What role, if any, does the history and culture of eating play in nutrition today?

Dr. Campbell claimed to fearlessly follow the evidence to answer these questions. So I decided to critically review his work – together with that of his vocal detractors – with as open a mind as possible, using this well-respected authority as an example to build or break my trust in the holistic approach to nutrition.

Dr. Campbell is as accredited a nutritionist as one can be: PHD in nutrition, Cornell tenured professor, published zillions of peer-reviewed paper in the most prestigious journals, received NIH research grants for decades. Yet he is clearly going against the grain of “regular” nutritionism, advocating for a broader, perhaps even philosophical, perspective on eating – while claiming to never leave science behind him. By seeing if his claims held water, I might be able to get some insight into the field at large.

In the coming 7 weeks, I will comprehensively review Dr. T Colin Campbell’s research about the WFPB diet and its implications for holistic nutritionism in general.

My findings are relevant only to this specific objective. Although I will briefly cover the work of other academic advocates for the diet, I do not claim to offer a conclusive opinion about the WFPB diet’s value, because new or other research may reach other conclusions. For example, this new 2024 study supporting plant-based diets1 must be independently evaluated.

Please note: Although much of what we’ll learn analyzes scientific and statistical data, I’ve written mostly in standard prose, not formal academic style. (For that reason, source references are in footnotes so as not to interrupt reading.)

Want to get ready for the ride? Check out this Appendix where I’ll introduce you to Dr. Campbell’s critics. I’m also including here the bibliography; these source references will apply for the entire series.

(We’re having some difficulties with this uploading this first PDF file. In case it doesn’t load for you, here’s a link to it as a Google Doc.)

Capodici, A., Mocciaro, G., Gori, D., Landry, M. J., Masini, A., Sanmarchi, F., Fiore, M., Coa, A. A., Castagna, G., Gardner, C. D., & Guaraldi, F. (2024). Cardiovascular health and cancer risk associated with plant based diets: An umbrella review. PloS One, 19(5), e0300711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300711

Such a cliffhanger. I can't wait. [I may need to stock up and some whole snack foods for the long haul.]