Festival of Foraging

How Sukkos's four species can help you know and appreciate Israel.

(One year after the following article was first posted, an adapted version was published here in the New Jersey Jewish Link.)

Dear Healthy Jew,

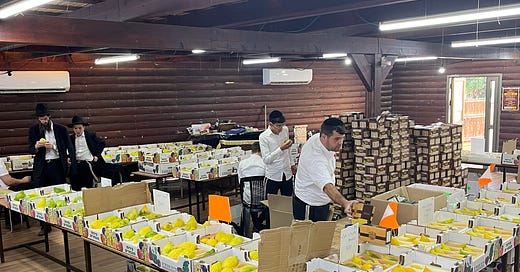

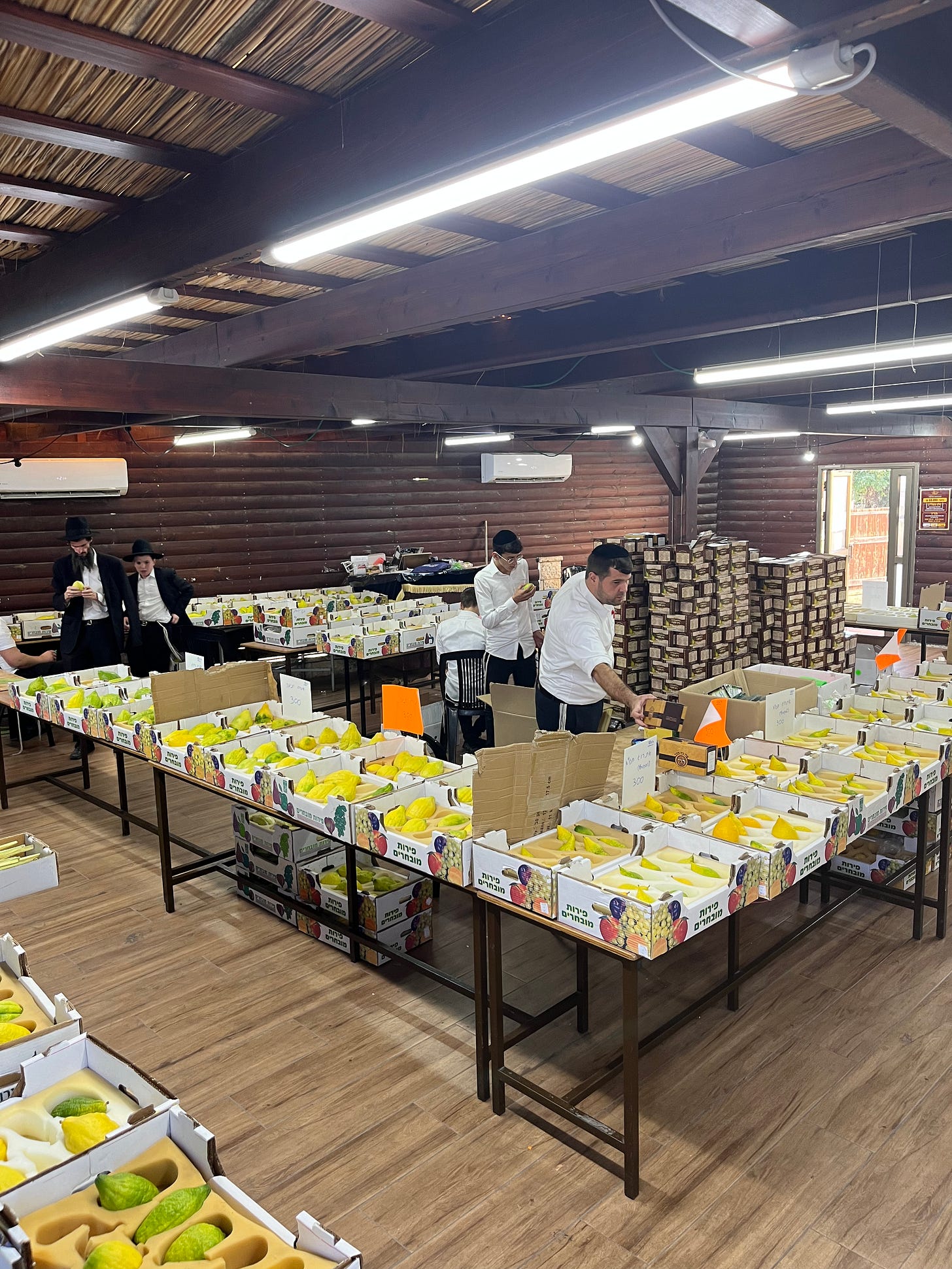

Lots of Healthy Jews are busy these days scouring stores for a stunning set of four plants: lulav (palm branch), esrog (citron), hadasim (myrtle branches), and aravos (willow branches).

It’s a great time to pause and notice what we’re doing: searching four random, mostly inedible plants.

For what? To take and shake them every morning for a week.

Pretty bizarre. How can this all possibly make me a better person, the world a better place?

Perhaps because of this mitzvah’s mysteriousness, Jewish sages taught lots of allegories and allusions about the four species. This detail represents that concept, we’re told, and that concept, in turn, symbolizes a sublimely profound spiritual principle.

Folks who like the practical side of things aren’t left out. Instead of plumbing the plants’ spiritual depths, they’ll invest tons of time and money in procuring an esrog without the slightest discoloring, a perfectly straight lulav whose top isn’t even a millimeter “open,” and hadasim whose three leaves revolve around the stem in a line as flat as the equator.

Let’s Get Real

Neither option – mysticism or minutiae - satisfies me. Living God’s word shouldn’t require a telescope to gaze at lofty realms, nor a microscope to count how many dots and spots my esrog doesn’t have.

I want to appreciate the Torah’s instruction to take and shake four plants, plain and simple. I’m not interested in abstract symbolisms and tapping into spiritual powers.

As we’d say here at Healthy Jew, for the four species’ esoteric messages and tiny details to have meaningful reality, we must first directly experience their elementary value right here and now, as four simple plants. Only then might that value extend to inform about underlying paradigms.

Perhaps these challenges spurred Maimonides (Guide 3:43) to choose this mitzvah to set the score straight on the Sages’ allegorical interpretations of the Torah’s stories and commandments. Although they are all true and important, Maimonides explained, don’t miss the basic biblical text because you’re pondering what each word represents in your body, your world, and other worlds.

Thankfully, Maimonides also offered an explanation that works for me.

Entering Israel

The Sukkos holiday celebrates God’s caring for us while we wandered the desert after receiving the Torah at Mount Sinai. But the Torah’s tale doesn’t end there: after Moses passed away, his chief disciple, Joshua, led the Chosen People into the Chosen Land.

What joy they felt upon entering a fertile, habitable country of their own after four decades in dry wilderness!

To remember that moment with gratitude, God instructed us to hold one of Israel’s most beautiful fruits (esrog), branches with the most fragrant smells (haddasim) and beautiful leaves (lulav), and the most beautiful grass (aravos).

These plants, added Maimonides, “were common in Israel in those days, so everybody was able to find them.”

Four Species, or Seven Species?

But I have a question.

Didn’t the Torah already characterize Israel’s blessed land with seven different plants: wheat, barley, grapes, pomegranates, figs, dates, and olives? The first fruits of these plants were offered every year in the Temple, and even today we recite a special blessing after eating them.

Why designate four new plants that have little practical use? Strangely enough, one of each group comes from the same tree: the palm offers its branches and dates.

A close look at Maimonides’ insight reveals the answer.

Sukkos isn’t the holiday that celebrates Jewish life in Israel. If it was, perhaps we’d indeed take and shake the species that Jews cultivate and thrive on in their country.1

Instead, Sukkos’s Israel component, the four species, appreciates the moment we entered Israel and found a beautiful country waiting for us.

Wow, thank you, God!

We weren’t yet thinking how Israel’s agriculture will support long-term settlement in organized societal structures. There will be plenty of time for that later.

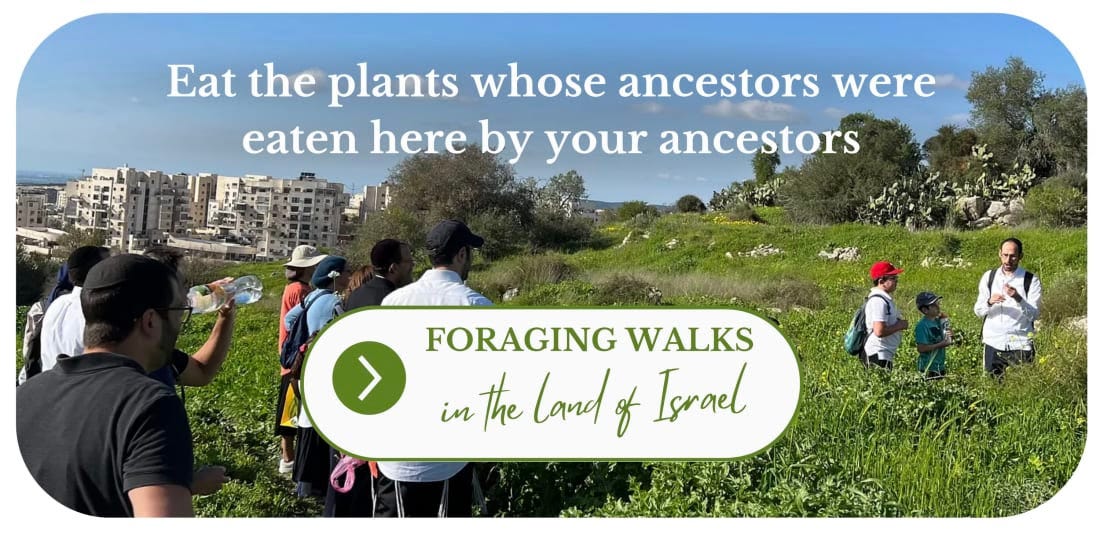

Right then, we were foraging.

Walking here, exploring there. Aware of this tree’s beauty and that bush’s fragrance. Tasting this fruit, holding that branch. Learning the land, becoming one with it. Exactly as we found it, no planting and harvesting necessary.

Festival of Foraging

The Torah calls Sukkos the Festival of Gathering, mostly referring to the end of the harvest season for cultivated grains and fruits.

But Sukkos is also the Festival of Foraging in Israel’s natural world.

Just like our forefathers over three millennia ago, we too can head out into Israel’s valleys, hills, and fields to forage for edible fruits, berries, and seeds. We can also learn the medicinal uses of many local plants.

In foraging, we connect with our heritage by eating the same plants whose ancestors were eaten by our ancestors, right here in this region or site mentioned in the Torah or Mishnah.

Archeological sites come alive: they’re not just a bunch of crumbling stones that the tour guides claim were busy metropolises thousands of years ago. Plant life fills the missing link between past and present.

Israel isn’t a bunch of buildings that happen to house Jews, connected by paved roads that said Jews drive on top of, always safely separated from the actual land. There’s plenty of concrete and asphalt all over the world.

Israel is a land, plain and simple. The four species tell the story of how we found it millennia ago, and how, if we’d like, we can find it today. Even if we need to be outside of Israel, the four species enable us, to some degree, to find and appreciate our land.

Thank you for reading Healthy Jew.

Here are 2 great paths to continue the journey:

Also check out this intro and index to explore hundreds of posts about our 3 Healthy Jew topics: Wellness with Wisdom, Land of Life (Israel), and Sensible Spirituality.

Finally, always feel free to reach out here with any comments, questions, or complaints:

I look forward to hearing from you!

Be well,

Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Naiman

In fact, there isn’t any biblical holiday exclusively about Israel. Only Chanukah, a later Rabbinic holiday, celebrates Israel’s redemption from the Greek Hellenists. Maybe another day I’ll share more about this.