Why Didn’t God Put Israel Next to Egypt?

Because freedom is a journey through a desert, not flipping a switch.

Dear Healthy Jew,

In less than a week, Jews all over the world will sit down to recount the Exodus from Egypt. We’re so used to used to the story that we might never have thought to ask why it needed to happen.

Why, actually, did the Jews need to leave Egypt? What would be missing if the humbled Pharaoh had set them free to serve God as they wished in an Autonomous Region of Goshen?

The Ramban (1194-1270) addressed this issue in his commentary on the burning bush story (Exodus 3:8). The Exodus, he wrote, wasn’t about liberation from Pharaoh, because “it would have been possible to save them in Goshen itself or close by.” The real reason we needed to leave was to conquer and settle the land of Israel.1

That’s a good, simple answer. It also fits well with the larger narrative of the Torah. Beginning from God’s first directive to Abraham – “Go to the land that I will show you” – all the way through Moses’ passing at the edge of Canaan, the Torah’s central theme is the Jewish people’s destiny to settle in their homeland, Israel. The Exodus was a formative chapter in the process.

Yet I’m still not satisfied. The Torah is a guide for life, not a geography textbook. If Israel isn’t inside or adjacent to Egypt, but an entire desert away, there’s a reason for that.

We needed to leave Egypt to get to Israel, but what are we to learn from Israel being so far away?

In fact, as things played out, the arduous desert trek to Israel was no trivial manner. Large swaths of the Torah tell of the troubles encountered and provoked by the Jewish people en route: thirst, hunger, fear of Canaan’s mighty warriors, and plain old complaining. When the spies told of the toughness of the land and its inhabitants, the nascent Israelites cried in fear to return to the safety of Egypt, and were sentenced by God to wander the desert for forty years.2

When all was said and done, the generation of Jews that left Egypt never made it to Israel, banging a dent in the Exodus’s completion that reverberates until today.

But what was the point of all this trouble? Couldn’t God have placed Israel on the other side of the Sinai desert?

For the Creator of the universe, moving a small country a few hundred miles down the road is no big deal. Passover would have been an Exodus-less holiday of freedom, the Pentateuch around 20% shorter, but everything else basically the same.

The following fable helped me unravel this enigma.3

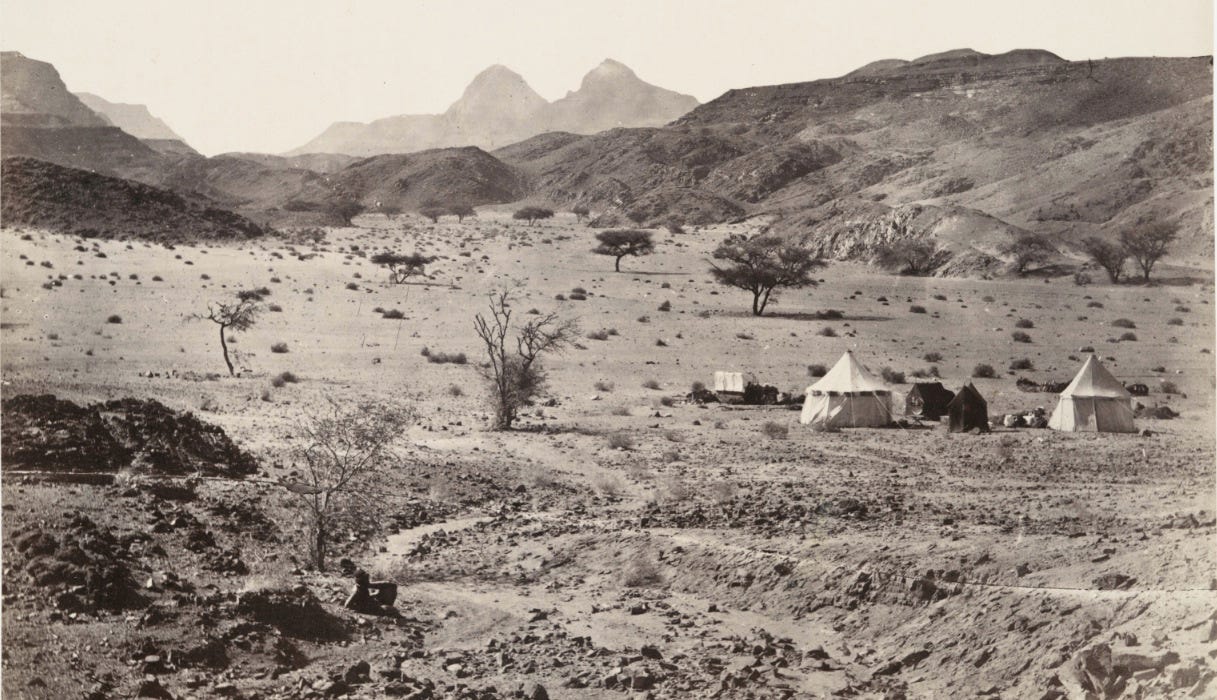

Many years ago, somewhere in the desert sands of Arabia, there lived a slave together with his master. One day, the master turned to the slave and said:

You have three choices. If you stay here, you will forever remain a slave. If you go on the Hadj to Mecca and walk around the Kaaba, I will make you a king. If you set out on the journey, but don’t reach Mecca, I will let you free, but as a regular person, not a king.

The slave’s path to royalty has three phases.

The final stage is circling the Kaaba, which will crown him a king.

Before becoming a king, he must endure a hard desert journey.

To survive the trip, he must prepare well. He’ll secure the best camel available, and gather as much food and water as possible. Even before that, he’ll spin string to sew a leather flask to hold the water that he’ll drink while traveling to Mecca.

Even while spinning string, the slave’s destination is the monarchy. Even the freedom he obtains by beginning the journey is only the first step toward his goal. And yet: with the simple act of walking out the door for the purpose of reaching royalty, he has already become a free man.

But our slave may never take that first step. He might spend the rest of his days spinning string in slavery, dreaming for the day when he’ll be prepared for the journey to royalty.

We might call the string-spinner a coward or a fool. But if we take a closer look at our own slaveries and freedoms, we might be able to identify with his folly.

At first glance, a freed slave has received a new status in the world, but otherwise remains the same person.

For this sort of freedom, the Jewish people could have stayed in Egypt.

On the personal level, whatever emotions, habits, or dependencies enslave us would simply disappear. Life would continue the same as before but without anger, lust, laziness, fear, selfishness, and all the rest.

Yet that’s not how gaining freedom really works. Until a slave sets out on the difficult journey to royalty, he remains spinning string in captivity, with freedom and kingdom still faraway fantasies.

No matter how many plagues the Egyptians suffered, their vast might – they were the material, cultural and spiritual superpowers of the ancient world – would have returned the Jewish people to servitude, because they never really left.

And whatever enslaves us to unhealthy habits and attitudes will bring us right back where we started, because we never really changed.

Freedom never comes from flipping a switch.

Real freedom is born with a paradigm shift: setting the goal of becoming a different person – of becoming a king, if not over a country, then over oneself. The slave must seek to inhabit a different place, literally or metaphorically.

Yet freedom doesn’t wait until the coronation ceremony. By taking one humble step in the direction of royalty, the slave has earned his freedom. He’s no longer stuck in captivity, but freely walking toward wholeness.

Still, that simple action can be terribly hard. Afraid of the journey’s challenges, he might spend the rest of making sure that he’s totally prepared.

So when God wanted to transform Egyptian slaves to Jewish kings, their new life must lie a desert journey away, enabling their winding, gradual process of growing toward wholeness.

What happened on the day of Exodus?

The Jews picked up and left Egypt. With faith and fortitude, they dropped everything and walked right out of Goshen into the barren desert, trusting in God to eventually deliver them to their kingdom.

Not only didn’t they spend years spinning string, they didn’t even wait for their bread to rise.

On that date, the fifteenth of Nissan, Jews all over the world continue to find freedom by eating unleavened matzoh, experiencing again the resolute rush to freedom laden inside every first step toward royalty.

Unfortunately, the Jews who left Egypt never made it to Israel. That generation gap heralded future fissures in the Jewish kingdom, resulting in the exile that we remain in today.

Yet we still live in the freedom our ancestors found by walking after God into the desert.

Whenever we’re stuck in a rut or have drifted off-course, our way out isn’t by willing ourselves to act, feel, or think differently, because whatever in us was holding me back will inevitably come knocking. Instead, we set out to grow from slave to king. But this awareness alone won’t free us: we take concrete action, purposefully moving in a new direction. Once we’ve taken the first step to royalty - which is often asking for help - we’ve chosen and acquired freedom.

There is no path to freedom. The path is freedom.

We might not know the route to our personal kingdoms. We might be afraid that we’ll fall on the way. Perhaps we will. We might not even make it to the end. But none of that matters. The Jewish people knew nothing of Israel except God’s report that it’s “the land of milk and honey,” and, as we saw, the Jews that left never found the Promised Land.

Yet they still found freedom in leaving, and so can you and I.

Before you leave, I just want to mention that Healthy Jew will be on break for the next 2 weeks due to the Pesach holiday (and because after 2+ years of publishing every single week, I’m due for a short vacation). I look forward to writing you again after we leave Egypt, from somewhere out in the desert.

Thank you for reading Healthy Jew.

Here are 2 great paths to continue the journey:

Also check out this intro and index to explore hundreds of posts about our 3 Healthy Jew topics: Wellness with Wisdom, Land of Life (Israel), and Sensible Spirituality.

Finally, always feel free to reach out here with any comments, questions, or complaints:

I look forward to hearing from you!

Be well,

Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Naiman

Please note: All content published on Healthy Jew is for informational and educational purposes only. Talk to a qualified professional before taking any action or substance that you read about here.

Ramban’s approach is also basically a verse in Deuteronomy (6:23), “He took us out from there [Egypt] in order to bring us up and give us the land that He swore to our forefathers.”

Ramban explains the burning bush conversation around this motif. Moses legitimately worried about the Exodus’s consequences, and God responded with a sign that eventually the newly forged nation will reach Israel: the Sinaic Revelation. In giving the Torah at Sinai, God forged a relationship of love with the Jewish people that will never be severed by temporary by lapses of trust.

I learned this fable in a very important but not very famous book of Jewish philosophy written by Rabbi Abraham ibn Daud (c.1110- c.1180) a prominent Andalusian scholar who lived in the generation before Maimonides, almost nine centuries ago. He apparently saw it in the writings of al-Ghazali (1058-1111).

Ibn Daud (and al-Ghazali?) interpreted the story as an allegory referring to stages of every person’s journey toward wholeness. His description is extremely important to understanding Healthy Jew’s mandate, and I hope to present it in the future. For today, however, we’re pondering the parable itself. The Rambam gave me permission to do this when he wrote (in his introduction to The Guide For the Perplexed) that many of the Torah’s allegories can be correctly understood on two levels: the simple lesson of the story, and the deep interpretations reserved for wise men. He likens this to a golden apple that’s covered with silver mesh lining: the lining itself is beautiful to behold, and upon closer scrutiny it’s revealed to also be the vessel that holds the golden apple.

One of the other commitments God made with the Jewish people was that saving the life of another comes before the keeping of Shabbat and the religious holidays. Which to me is is all apart of the journey through a desert. In the US I'm seen as a 1st responder as I'm a ham radio operator and a Skywarn storm spotter and in ARES/RACES. It is also why I believe in growing as much food as you can yourself. Even in window boxes.